Tsavo lions have long been notoriously known as man-eaters. Smaller than their Mara brethren, Tsavo lions have smaller manes or no manes at all thanks to their harsher environment. While most lion prides will have a large number of females with a pair of males among them, Tsavo lion groups are smaller, with only one male claiming breeding rights.

As the slave trading roads developed through Tsavo, many traders pushed their captives hard across the barren wasteland. When a slave died, they were simply left behind, becoming an ample meal for scavenging predators. Many believed this gave the Tsavo lions an early taste for human flesh, one that would stay with them for the incoming British in the late 19th-century.

Soon after Lieutenant Colonel John Henry Patterson arrived to lead the construction of a railroad bridge in 1898, lion attacks ravaged his worker's camp. Striking in the night, a pair of lions with a seemingly insatiable appetite stalked the builders. Screams could be heard in the dead of night as these ferocious predators pulled men from their tents into the wilderness.

Some accounts state that 135 people were eaten by the two lions that year, but company reports place the official figure closer to around 40.

This figure, however, didn't account for any nearby villagers that may have been killed by the lions, making the true number a mystery.

The terrified villagers gave the lions the names, The Ghost and The Darkness.

Lieutenant Patterson, who had hunted tigers in India, was put in charge of stopping the lion's massacre. He erected thorn barriers,

lit bonfires at night, and enacted curfews, but the attacks only seemed to get worse. The workers grew increasingly superstitious and mutinous.

In December 1898, Patterson’s changed his approach. Summoning the workmen at their camp to gather tin cans and noisy instruments, he had them form a

semicircle and advance into the bush. Patterson positioned himself behind an ant hill and waited for the lion to walk past.

The lion came within 15 yards of his position, but Patterson's double-barreled rifle misfired. Flustered, he hadn't fired the left barrel, but the noise

created by the workmen had disoriented the lion, giving Patterson enough time to shoot again. This shot hit its target but didn't kill or wound the lion.

The following evening, Patterson built an improvised treestand with a chair perched above the ground and set a dead donkey carcass as bait. Armed with his huge rifle, he killed the first

man-eater with two bullets.

The second man-eater's death was perhaps even more dramatic. Patterson used goats as bait, but in the pitch dark,

he fired bullets wildly.

He set up another blind above goats and waited again. When the lion approached, he fired his smoothbore and connected.

The lion dashed into the bush and died.

When the story got out, Patterson became an international hero and restoring faith in his workers the construction of the bridge continued.

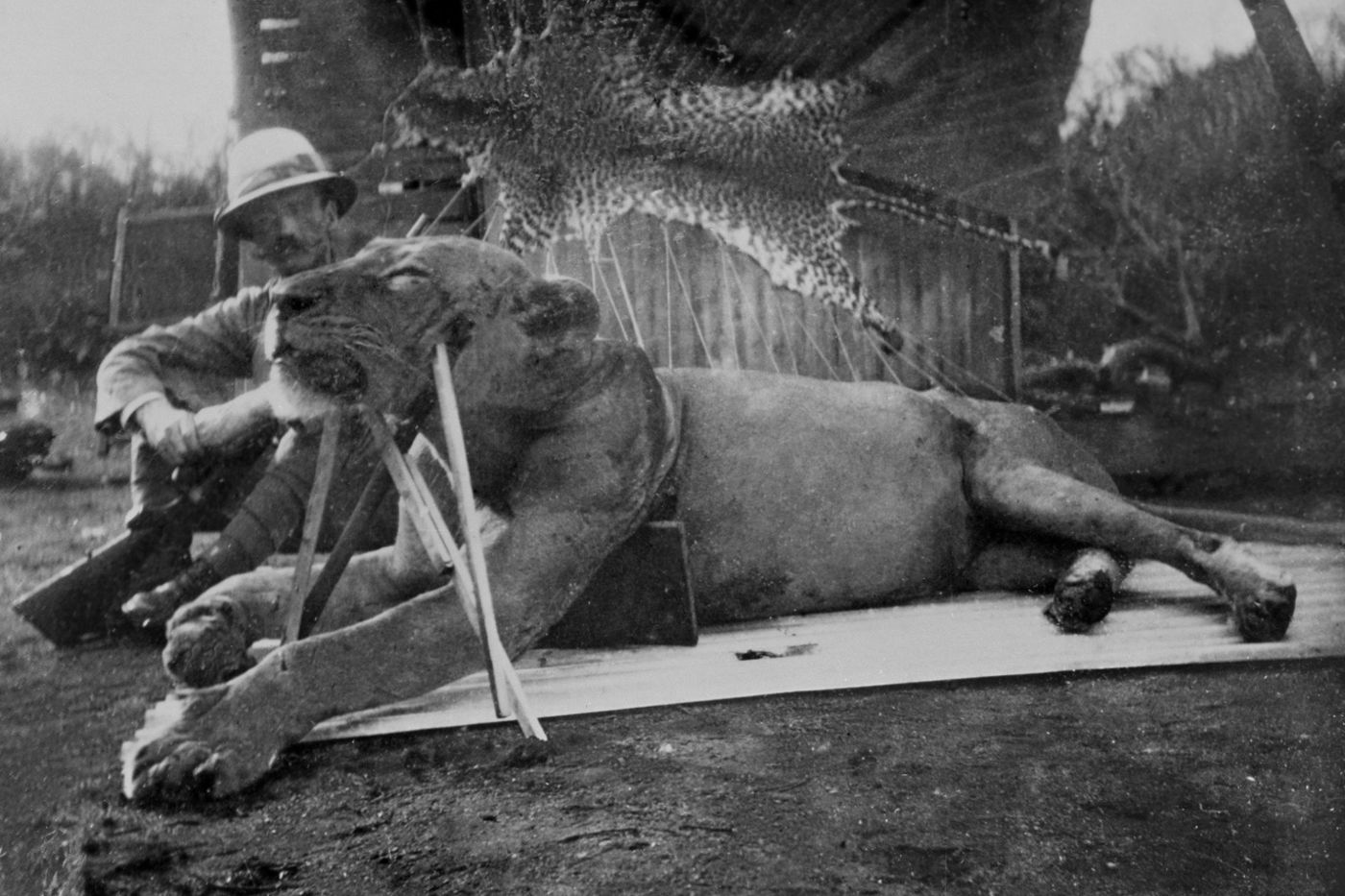

The lions were stuffed, eventually making their way to Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History.

At the time, much romance and superstition were used to explain the Tsavo man-eaters' behavior. An incorrigible appetite or taste for human blood was chief among Patterson's own account of the animals' reasoning. He surmised that the careless burial practices in the region had meant the lions often scavenged human remains, enticing them to dine on humans.

Since the lions' remains were preserved, scientists have been able to examine their mouths and discovered that damaged jaws may have accounted for their behavior. With evidence of an abscessed tooth, they believe one of the lions may have had trouble hunting larger prey, and might have been forced to raid the camps for food.